The Gemini: ‘A cess-pit run to make money out of sexual filth’

Lizzie Osborne

To mark LGBT History Month, the SAHGB's LGBTQ+ Network is delighted to present an excerpt from Lizzie Osborne’s ‘Cesspits of Filth’ project. In this investigation of Huddersfield’s Gemini club, the ‘Studio 54 of the North’, Osborne writes that the project aimed to 'reappropriate British vernaculars in a way that expressed the subliminal coding of desire and epxression’ by offering a spatial and experiential reconstruction of the former queer night club. The project formed the basis of Osborne’s MArch Dissertation, and was awarded the RIBA Presidents Award Dissertation Medal Winner, 2020.

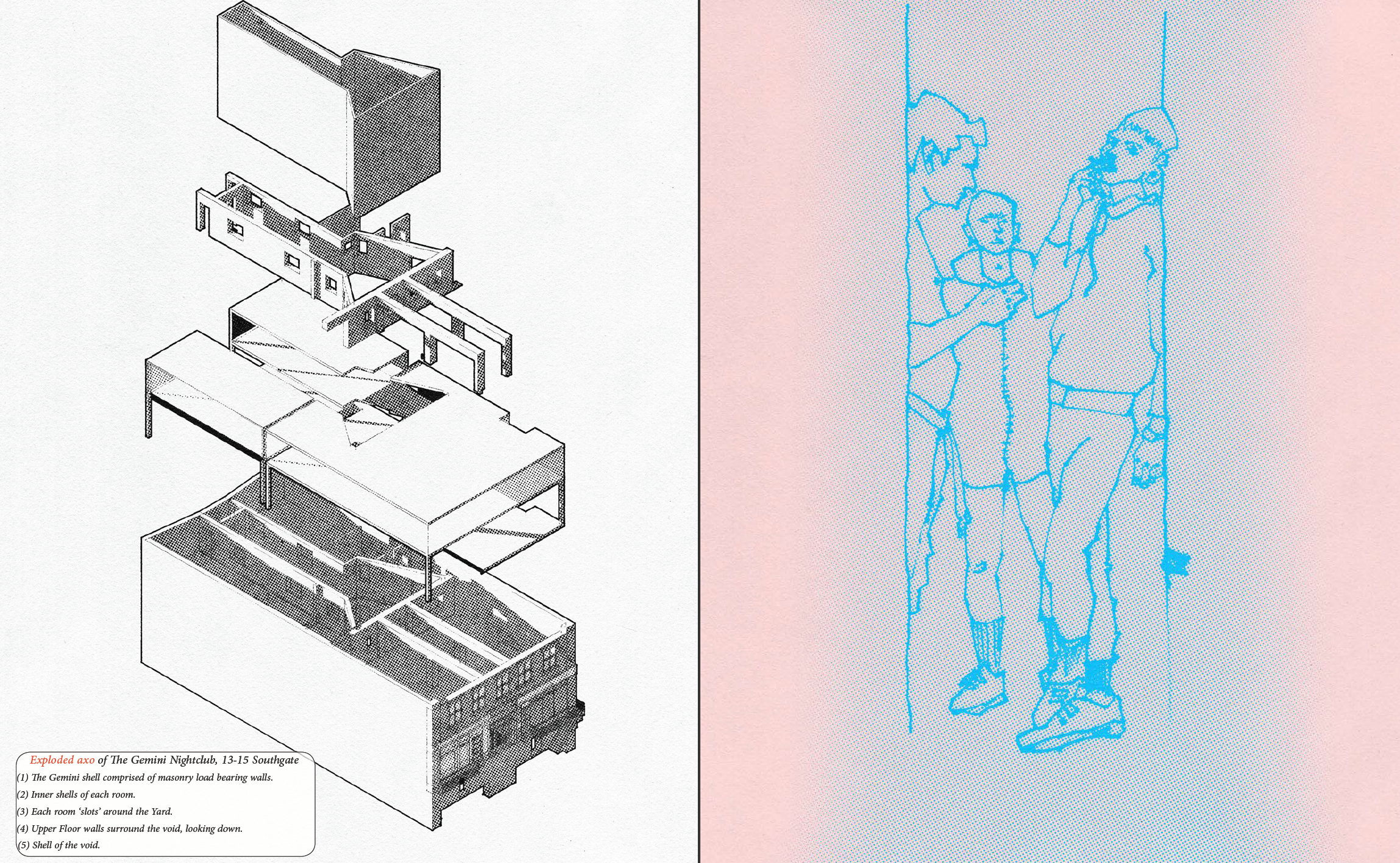

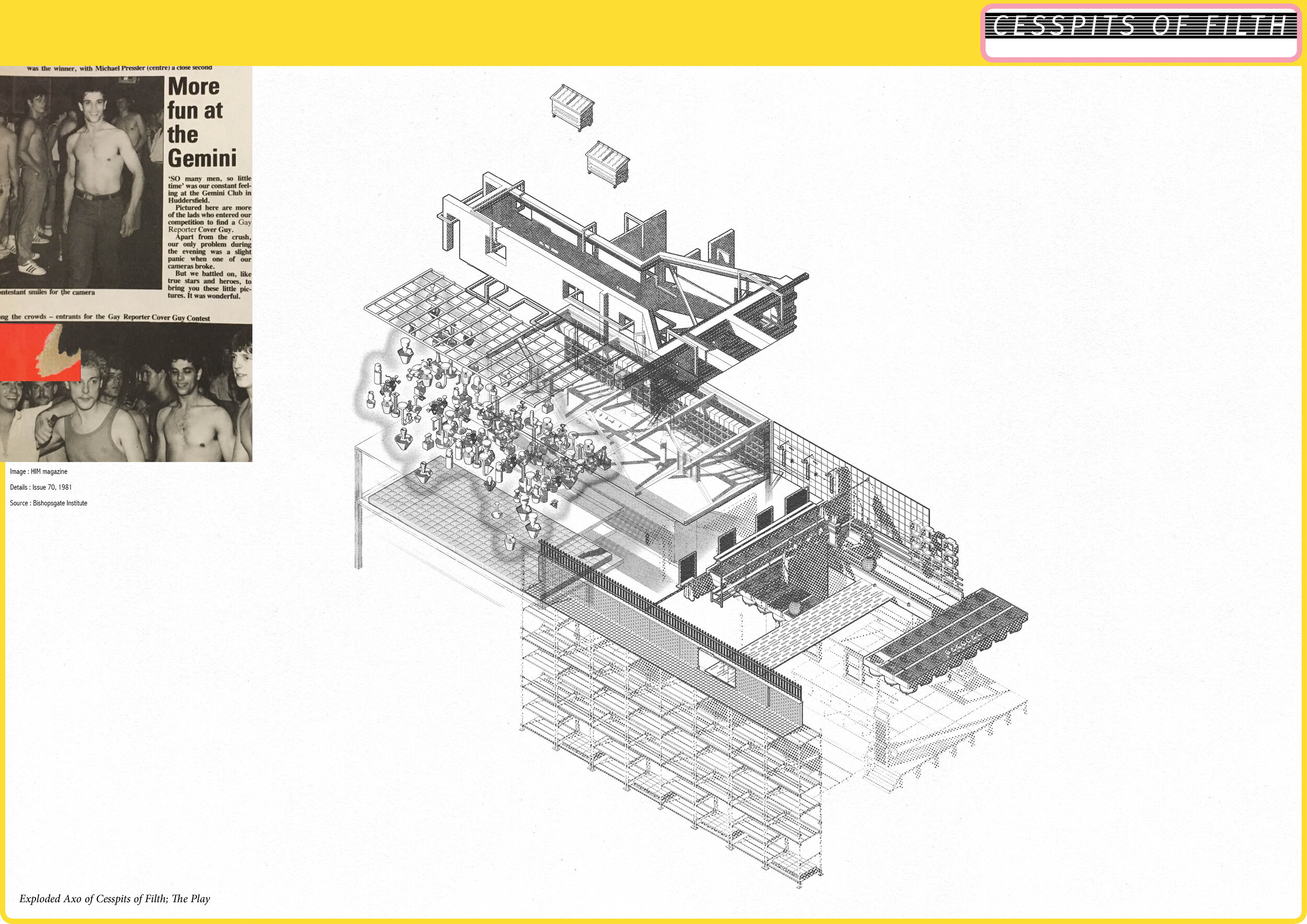

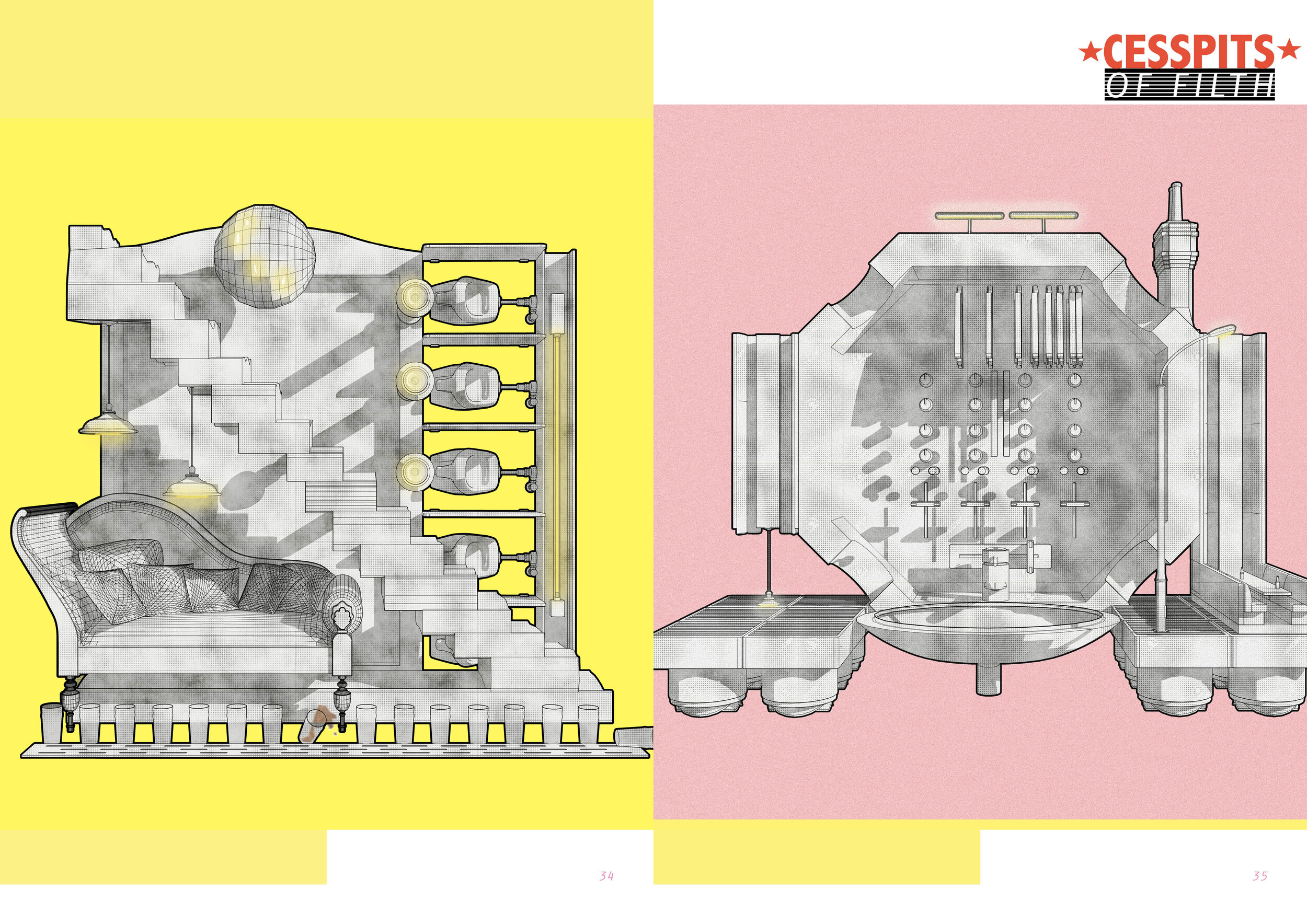

‘Cesspits of Filth’ is a dissertation which combines my work as a Master’s of Architecture student with my love and research of local queer histories. The story of the Gemini club was manifested through collected oral histories and newspaper clippings, but was also visualised through the popular 3D-modelling programme SketchUp. Through Kirklees Council’s planning portal, I was able to sift through old planning applications to track the histories and changes to the structure of 13–15 Southgate, Huddersfield – its journey pieced together for me through the changes in its walls, its staircases, its windows. Along with the first-hand accounts, I was able to map different parts of the space: this was where the dance floor was, this was where the cloakroom was, this was the yard where they were arrested for indecent acts.

Besides allegations of it being ‘no more than a cess-pit run to make money out of sexual filth’ (Huddersfield Examiner, 1978), the Gemini bar, a gay nightclub located on Huddersfield’s Southgate, along the ring road, was once described as ‘the Studio 54 of the North’ (see Stevan Alcock, Blood Relatives, 2017). The only obvious remaining evidence of its existence seems to be a Facebook group with 43 members called ‘Remembering Gemini’. The posts uploaded by its users include: a clipping from the Gay Reporter with a playlist of ‘Gemini Stompers’; a few photos of the men who managed the bar; and various newspaper articles, mainly from the Huddersfield Examiner, regarding the club’s demise following its liquor license being challenged by police in 1981. The club itself was opened by John Addy, and his partner Anthony. Addy now runs the factory of one of Europe’s largest manufacturers of Alkyl Nitrates, commonly known as poppers, Pure Gold, based in Huddersfield.

What is it that makes a space ugly? Is it dirt? Is it filth? Is it the awkwardness of its arrangement? Is it the type of people that frequent the space? Conversely, why do some find joy in a clumsy, make-shift environment? Through the collective building of shared experience, maybe we are the architects, builders or contractors of our ‘homes’ and chosen family. Regardless of its architectural output, queer joy is inherently radical in a capitalist society that prioritises competition and profit above connection and community sharing. The analogy of a nightclub might be a better way of describing this spatially: a gathering of careless bodies, where the venue itself might be insignificant and unimportant.

Huddersfield’s Gemini club was located against the backdrop of the town’s red-light district – nestling itself geographically in alarming proximity to the Yorkshire Ripper murders of the time. With Peter Sutcliffe’s string of murders of women in the North, the cultural and moral panic connecting gay men with AIDs in public spaces, the police beat patrol on the town’s periphery, and the dissolution of Huddersfield’s industrial landscape, we can almost imagine the chokehold of the ring road as a tapestry of panic, an incubus of an agoraphobic psyche.

The club’s popularity steadily increased – queer communities around the country would travel great distances for a night out in Huddersfield. Neighbouring cities, particularly Leeds and Manchester, would organise coach departures on Friday and Saturday nights to the club. Although it remained a small and unassuming building bordered by Huddersfield’s new ring road, developed during the ’70s, its growing popularity led to growing surveillance. A series of raids took place at the club, with Huddersfield’s police commissioner at the time describing it in a report as a ‘cess-pit of sexual filth’. In an occurrence quite commonplace at the time, and not limited to Huddersfield’s Gemini, patrons of the bar were booked, fined, names taken: no small thing in a period when being outed could be life-threatening. A tension developed between the patrons and the outside world related to the growing proximity of police surveillance, which undoubtedly had a knock-on effect on attendance, resulting in owner John Addy being pushed to burnout. That summer, the London Pride parade was even moved to Huddersfield in protest against the raids, a final attempt to save the space before Addy eventually gave up and declined to renew the liquor license in 1981, leading to the end of his ownership of the club. After undergoing a refurb, when a new dance floor was installed and the entrance stairwell painted a new striking red, the Gemini was reopened by new co-owners. Its doors were officially closed in 1983.

It is no coincidence that the demise of the Gemini club coincided with the AIDs crisis in the UK. The implications this had on queer spaces take many different forms, but most apparent in our discourse on surveilled spaces is the eradication of ‘disease’ sought by authority at the time. It certainly amplified the dissolution of these spaces, with the connotation being that places in which gay men gathered were incubators of disease, were ‘cesspits of filth’, to be exterminated in a systematic approach from police and social structures. ‘The queerest space of all is the void’, queer-spatial theorist Aaron Betsky writes – and from his writing and also from the general discourse on the AIDs crisis, it might be assumed that the surge of new queer spaces in the late 1970s and early 1980s were swiftly eradicated due to this health epidemic.

The Gemini and other spaces of ‘same sex desire’, pre-AIDs crisis, were already nestled within pre-existing voids in the urban fabric: discrete but ‘electric’ places, bin yards, parks, basements. However, there was a fleeting moment in which we practised, with our vernacular skills of survival, how to appropriate these unwanted voids – spaces left behind by the city, the town, recycled into composites of charged bodies. Therefore, the void that Betsky references here must be a depiction of these bodies after the flesh and skin had been lost. The epidemic of death and loss that follows us and the spaces we frequent leaves imprints of grief within our queerest of geographies. The Gemini and its story are not unique in this sense, but their uniqueness inherently lies in the fact that this space was not located in our commonly researched metropolises like New York or London. The insufficient way our stories are reflected in mainstream media sparks the urge of vengeance to retell these stories using our own narratives of vernacularism and queer space, outside of the obvious margins of the histories we are taught.

Lizzie Osborne (they /them) is a recent graduate of their part 2 in Masters of Architecture. Lizzie’s focus for their masters was centred around reappropriating architectural histories local to Huddersfield in an attempt to archive and reimagine local queer spaces and stories.